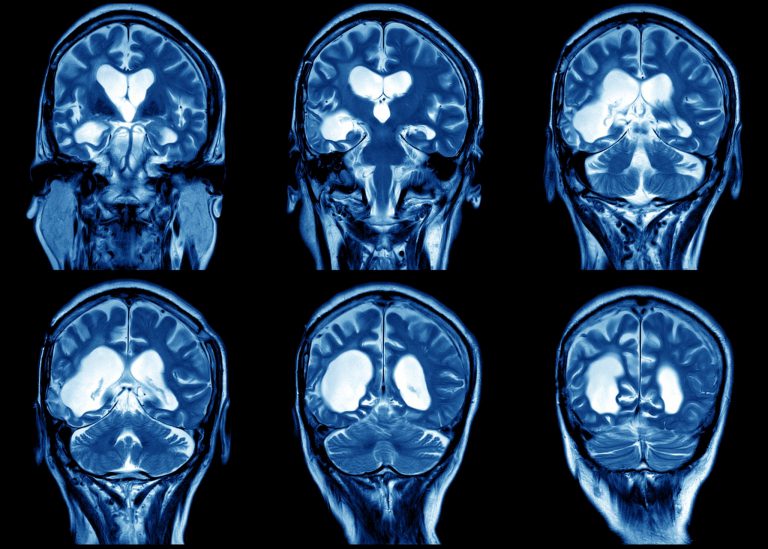

Researchers from New York University (NYU) have discovered evidence of autism in the structure and impairments of blood vessels in the brain.

The study, titled “Persistent Angiogenesis in the Autism Brain: An Immunocytochemical Study of Postmortem Cortex, Brainstem and Cerebellum”, published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Scientists at NYU find new vessel for detecting #autism https://t.co/G3aYpN4ilP

— UCLASemelFriends (@UCLASemelFriend) December 17, 2015

“Our findings show that those afflicted with autism have unstable blood vessels, disrupting proper delivery of blood to the brain,” says Efrain Azmitia, Professor of NYU’s Department of Biology and the study’s senior author.

Co-authors include Zachary Saccomano, a graduate of NYU; Mohammed AlzooBaee, an NYU undergraduate student; Maura Boldrini, a research scientist from the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University; and Patricia Whitaker-Azmitia, a Professor in the Department of Psychology at Stony Brook University.

2015 learning disability in-patient census figures at https://t.co/WUorFVwr72. 3000 people with learning disability or autism in hospital

— Gyles (@Gyles) December 17, 2015

The researchers analysed post-mortem human brain tissue, using a control of ‘normal’ brains as well as a number which had been granted the autism diagnosis, though none of the scientists were aware of which sample was which.

“In a typical brain, blood vessels are stable, thereby ensuring a stable distribution of blood,” explains Azmitia. “Whereas in the autism brain, the cellular structure of blood vessels continually fluctuates, which results in circulation that is fluctuating and, ultimately, neurologically limiting.”

People with autism are less likely to catch yawns. The more severe their condition, the less common the behavior gets.

— Google Facts (@GoogleFacts) December 17, 2015

The scientists found that angiogenesis, or the creation of new blood vessels, occurred in the autistic brain tissue but not in the normal sample. This suggests that the autistic brain is repeatedly producing blood vessels, with constant fluctuations that cause instability in blood flow to the brain.

They also found the autistic brains to contain greater levels of nestin and CD34- proteins that control the angiogenesis process- compared to the typical brains.

Ten Celebrities With Autism… https://t.co/WB8S6UoW5Y

— Fact (@Fact) December 17, 2015

“It’s clear that there are changes in brain vascularisation in autistic individuals from two to 20 years that are not seen in normally developing individuals past the age of two years,” concludes Azmitia. “Now that we know this, we have new ways of looking at the disorder and, hopefully with this new knowledge, novel and more effective ways to address it.”

Image via Shutterstock.

Liked this? Then you’ll love these…

Discovery of mass gravesite halts UGA expansion

Harvard University study finds new dangers linked to lung disease