Our future depends on what we built in the past and keep in the present — but what should we preserve? Monumental structures like the Baroque cathedrals in Latin America, the Palace of Versailles in France, and India’s Taj Mahal mausoleum are obvious choices. But what about less grand buildings and sites? Should we protect the stories and values encoded in these living artifacts?

Both the questions we explore and the answers we uncover are essential to future generations. Cities, landscapes and countries without the familiar remnants of our past are hard to imagine and, worse still, devoid of their power to give us profound wonder and pride. Preservation ensures not only that our stories live on, but also new narratives can be layered upon the old. In historic Philadelphia, the US’s first UNESCO “World Heritage City,” buildings from the 1700s live side-by-side with modern buildings, creating a collage of past and present times and places.

Preserving cultural heritage is also a catalyst for sustainable development, economically, socially, and environmentally. As recognized by the 20th General Assembly of the States Parties to the World Heritage Convention, the restoration and rehabilitation of historic properties have the potential to contribute directly to neighborhood revitalization, helping to alleviate poverty and combat social inequalities.

And, as preservationists often say, “The greenest building is the one already built!” Studies have shown that the construction and demolition of buildings accounts for 48% of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Reusing and retrofitting already existing buildings constitutes “recycling” on a grand scale, reduces these emissions dramatically and are an indispensable source of renewable energy; avoiding the environmentally costly route of constructing new buildings and using up open space. This “back to the future” approach not only preserves but also re-envisions and re-purposes historic buildings and sites, defining preserving the past as a template for a sustainable future.

At the Thomas Jefferson University College of Architecture and the Built Environment, the emphasis is on three core values: social and ethical responsibility, stewardship of the environment, and design excellence. The MS In Historic Preservation program focuses upon the relationship between rehabilitation of historic buildings and sustainability applied to projects at multiple scales, ranging from the micro level of individual buildings to the macro level of community preservation planning. Heritage properties are not viewed as disembodied relics of the past but as possibilities for adaptive reuse and retrofitting, as models of energy efficiency, and as part of the cultural fabric of a community.

At Jefferson, every program is customizable and flexible. Source: Thomas Jefferson University

Applicants from a broad spectrum of undergraduate disciplines — including architectural history, art history, archaeology, urban planning, architecture and design — bring diverse perspectives to this 49-credit program. As they explore a curriculum that emphasizes restoration and rehabilitation, students gain the know-how to assume leadership positions upon graduation.

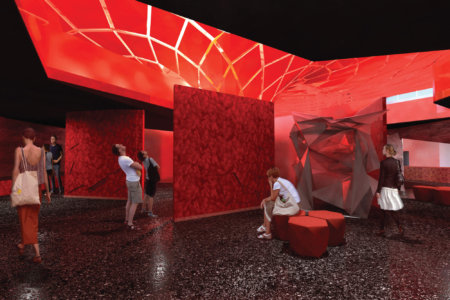

Contributing to this growth is the development of skills fundamental to assess the condition and evolution of buildings. What’s more, students learn how historic structures order the urban fabric, contribute to healthy communities, and facilitate “place-making” as a catalyst for community revitalization. Several opportunities are available for these future sustainable innovators to apply evolving technologies used to manage, document, and interpret culturally significant structures and places, such as LiDAR and virtual reality.

The best part? The experience is customizable. Enrolled students will be able to select one of two tracks — Research and Documentation or Preservation Design. The first is open to students from all academic backgrounds looking to take on the challenge of becoming a preservation planner or strategist; whereas the second was designed for those with a bachelor’s degree in architecture looking to become preservation architects. Through both tracks, the option to pursue doctorate studies upon graduation remains.

Students will also be able to specialize in a field compatible with their professional goals, taking their pick from the college’s extensive line-up of graduate courses such as sustainable design, geographic information systems, architecture, or real estate development.

The historic yet modern city of Philadelphia is the first UNESCO World Heritage City in the US. Source: Photo by Bence Pöcze

Joining Jefferson means taking in the same wonders notable architects such as Louis Kahn and Richard Neutra once did. The former, one of America’s most famous architects, was headquartered here. The city of Philadelphia, a hub of modern architecture in the 50s, is also home to dazzling tourist attractions such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the famed Wanamaker Building, the Georgian-style Independence Hall, the iconic Vanna Venturi House, and many more.

“Philadelphia is rich in its history — both culturally and socially,” enthuses Jefferson student Breanna Sheeler. “It’s also one of the fastest developing cities. As students and future professionals, we get to redefine the way Philadelphia is growing and shaping its landscape.”

Jefferson’s new Center for the Preservation of Modernism is an added bonus. One of the key challenges the industry faces today is the preservation of modern and mid-century modern architecture and sites. Program director Suzanne Singletary describes this as “the next frontier within the profession.” Preservation protocols tailored to the characteristic problems posed by buildings and sites dating from the 1930s to circa 1980 are currently lacking. Spotlighting this period is the mission of Jefferson’s Center for the Preservation of Modernism.” The Center also serves as a meeting ground for the larger preservation community, offering lectures and symposia that address pressing issues facing modern structures and sites.

Exemplar of Mid-Century Modernism, Richard Neutra’s Hassrick House, 1959, owned by Jefferson, is the face of the Center for the Preservation of Modernism. Photo: Hussain Aljoher

Philadelphia may be the ideal location for case studies in the field, but at Jefferson, international exposure never takes a backseat. That said, students can opt to study the preservation of modernist architecture abroad at the renowned Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany or at the Giuseppe Terragni Archive in Como, Italy too.

Are you ready to begin a transformative, experiential and rigorous education in historic preservation? Learn more about Jefferson’s innovative program here.

Follow Thomas Jefferson University on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube